[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″ offset=”vc_hidden-xs”][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-main”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

I write this from the perspective of one who has generally benefited (i.e. maintaining significant bond exposure) throughout this cycle by riding the wave of lower and lower interest rates. Many times along the way, though, it has been tempting to join the annual calls that we have reached the end of the ride and that higher yields are around the corner. Again and again, yields made new bottoms and made us thankful for owning normal fixed interest rate bonds. From my seat though, we have reached a point that warrants a serious consideration for interest rate risk.

I point to a couple of things that point to the current risks – none of which are directly related to US Federal Reserve interest rate hikes. I would note however that I do think there is higher than market consensus odds for hikes in 2017.

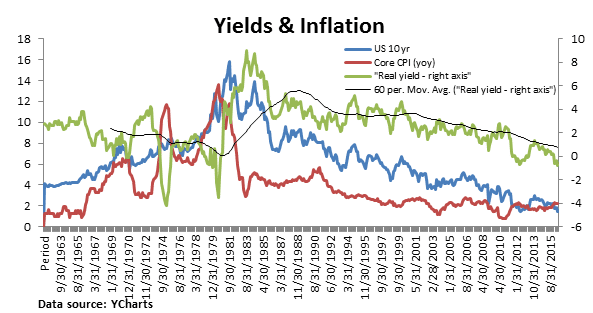

Negative Real Rates

The first threat I point to is that of yields on 10 year US treasuries again falling below core inflation. We call this a negative “real” interest rate. This isn’t unprecedented, but past instances of negative real rates were short-lived. Yields have been chasing inflation lower since Federal Reserve Chairman Volcker dropped the hammer in the early 1980s. We are now as far off trend as at any point since the months leading up to the big 2013 correction!

The measure of inflation here, Core Consumer Price Index (CPI), might very well moderate as we move through the back half of 2016, but the low yields suggest a good portion of moderation is already to be expected. The risks at this point are that we edge back up in real yield, a good portion of which could come from higher nominal rates. The regular or “headline” Consumer Price Index (CPI) gets a lot more attention and for good reason. With headline CPI much closer to 1%, the “real” real yields aren’t yet negative at the 10 year mark. However, as the impact from the collapse in crude oil fades, we might just see core and headline meet somewhere in the middle and closer to 2%.

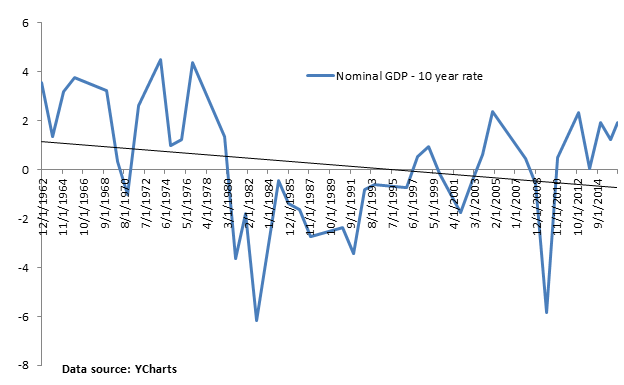

Bonds & the economy: relationship restoration

The next factor I consider is the long-held relationship between economic growth as measured by nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the yields on 10 year bonds. Nominal GDP growth measures overall growth before they subtract out inflation to get to Real GDP. Demographics in the US have shifted this trend down slowly over time as boomers have moved from being borrowers to being savers. Still, the relationship between nominal GDP and 10 year rates has been fairly tight over time. Instances where the difference went much beyond +/- 1% were quickly corrected. Runaway inflation in the 70’s took nominal GDP super high – a sort distortion to the relationship that could happen again. But I wouldn’t make that a base case and I doubt that would be too kind to bonds, either. With a nominal GDP of around 3.5% and a bond yield of around 1.6% the difference is approaching 2%. This kind of stretch is near the highs of this generation and we could certainly either see the economy and/or inflation soften without much give in yields, or we could experience a shock higher in rates.

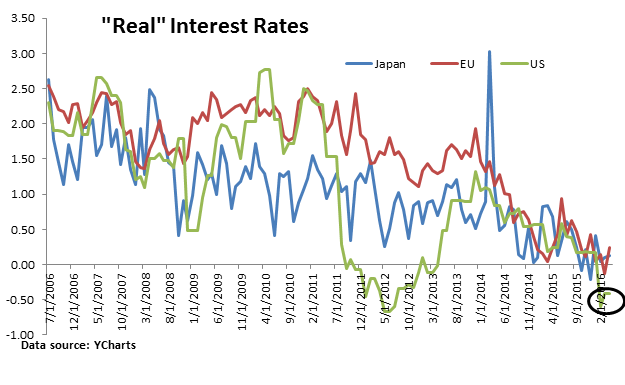

“But look at Japan and Europe, the US is High Yielding”

A common argument for hanging in there with treasuries is the comparisons to the rest of the world. The argument is an appealing one that suggests that rather than earning less than 0% in Japanese Government Bonds (JGB’s) or German bunds, you should grab the 1.6% still available in the US. While racing out to earn a negative yield in those foreign bonds shouldn’t be in the cards, I don’t think the argument fully appreciates the significance of investing in different currencies with potentially vastly different inflation and growth characteristics. The chart below compares the differences in “real rates” (like is done above for the US) among the US, Japan and the EU as a collective.

The deflationary drag in these countries shows that rates are low in these countries for a good reason. Based on this relationship, we are actually lower than norms would suggest! Though we could hover lower in real rates for some time, hopefully this at least throws a little cold water on the “US is a high yield” thesis.

Together, these factors don’t provide me with a case to go outright short bonds or even all out of bonds. However, they firmly warn me, and perhaps you, that we are susceptible to a shock in rates higher.

Disclaimer: Do not construe anything written in this post or this blog in its entirety as a recommendation, research, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. Everything in this post is meant for educational and entertainment purposes only. I or my affiliates may hold positions in securities mentioned in the blog. Please see my Disclosure page for full disclaimer.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column offset=”vc_hidden-lg vc_hidden-md vc_hidden-sm”][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-main”][/vc_column][/vc_row]